Proposal: The Wealthiest Among Us Should Pay Their Fair Share

It is a fundamental tenet of a just society that the burden of taxation should be shouldered most by those best able to afford it. In previous decades, this was clearly reflected in the federal rates of taxation levied against the wealthiest in our society; the top marginal income tax rate was over 90% less than a century ago, and was over 70% as recently as the Carter Administration.

Despite the enormous growth in the assets and influence of (in the case of the latter, partly because of) the rich, the progressiveness of the federal tax code has declined precipitously since 1980. In fact, by 2019, the effective tax rate paid by the wealthiest people in US society fell below the average rate paid by the bottom 50% of Americans for the first time in history, producing a system that is in fact regressive. Far from taxation being proportional to the ability of the taxed to afford it, our tax system now magnifies income inequality and harms the poor to the benefit of the rich.

BCS considers this to be not merely a serious problem, but a perverse one. Just ten short years ago, our country was at the depths of the deepest recession in nearly a century, caused in no small part by the depredations, predatory behavior, and excessive risk taking of the financial sector, an industry of, by, and for the wealthy. There were few repercussions then, and today what we have to show for that public benevolence is a society with the worst income and wealth inequality in its history and a federal government that largely reflects the interests of those who placed us in crisis to begin with.

With this in mind, BCS believes it is time to make the wealthiest among us pay something closer to their fair share, and to use the revenue gained from doing so to make Brattleboro a better place to live, own a home, and do business in. We believe this is best accomplished through the creation of a modest local tax targeted towards those at the top of the income distribution, particularly those making more than $1,000,000 per year, an amount that is nearly 20 times the median income in Vermont.

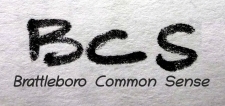

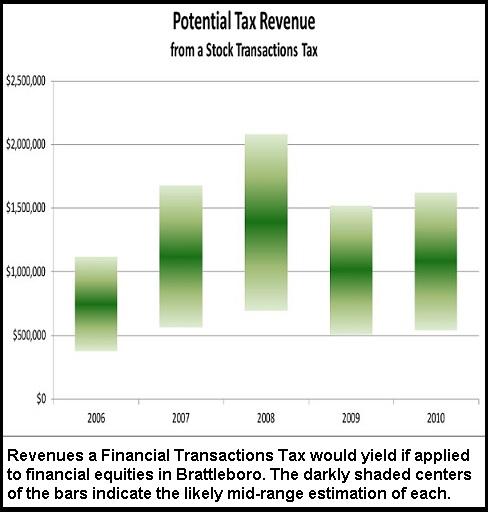

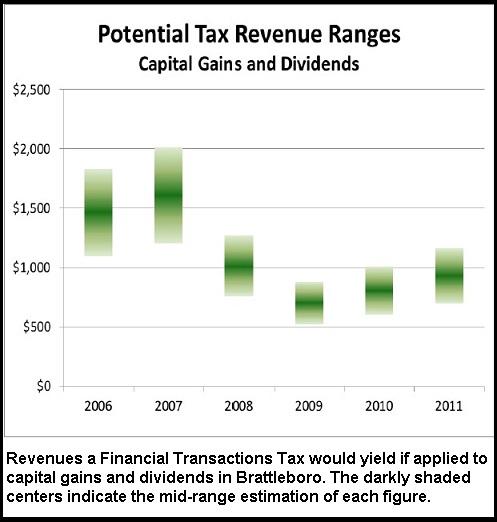

The figures at right were calculated for BCS by economist Gwen Hallsmith in 2010. They provide an indication of the scale of potential municipal revenue from Financial Transaction taxes. (Click an image to enlarge)

BCS’s latest research was done by Adam Marchesseault in 2020, and includes statewide figures for Vermont as well as local figures for Brattleboro. Read his report HERE.

Specifically, BCS is researching the merits and drawbacks of four different types of taxes, which could be levied separately or in conjunction with one another, in an attempt to maximize the economic and social benefits to the community and mitigate unwanted effects like harm to businesses and retirees or migration out of Brattleboro by the wealthy.

We are examining the options of:

- A Millionaire Income Tax, the creation of a tax bracket that applies a supplementary income tax to personal income over $1,000,000.

- A Financial Transactions Tax, essentially a sales tax on things like stock trades that discourages high-frequency trading and promotes long-term investments.

- A Wealth or Portfolio Tax, taxes that are respectively levied on the total assets or financial holdings of an individual above a certain amount.

- A Local Capital Gains Tax, the creation of a local tax on profits from selling financial assets in addition to existing federal and state Capital Gains taxes.

Our recognition of the pernicious nature of income inequality and the tax system is not a call to “Eat the Rich”, but rather a recognition that our society only works when its resources are marshaled efficiently to accomplish our collective goals. With that in mind, BCS is hoping that the passing of new taxes on the wealthy in Brattleboro will provide the revenue necessary to do things like:

- Reduce or eliminate the property tax, encouraging people to move to and buy homes in Brattleboro

- Create a Climate Change Emergency Fund, safeguarding Brattleboro against sudden costs resulting from local problems or disasters caused by climate change

- Invest in public resources for everything from homelessness to business development and entrepreneurship

- Invest in renewable energy and the city’s infrastructure

Vermont History of Taxing Wealth and Property

Originally, both the state and the towns and cities taxed property, as a way of reaching income, as property was the surest indicator of wealth, and income. The larger the farm, the more sheep or milk cows or crops, the wealthier the farmer was. This was not as effective a tax as a direct income tax, because of the inexactitude in reaching the true sources of wealth, but before income taxes, the property tax was what the State of Vermont relied on as sources of revenue.

Vermont taxed what you owned, not what you made. The property tax covered land and buildings, watches, clocks, cows, dogs, linen, furniture, wearing apparel, tools, inventory, and people, through a poll tax. In 1855, Vermont first required nonresident taxpayers to disclose the shares of stock in steamboat and transportation companies. The disclosures were then added to the grand list of the respective taxpayers, and subjected to the property tax. The law provided the tax bill would constitute a lien on the stock, which could be foreclosed by the local delinquent tax collector. Taxes raised on this form of wealth were then distributed to the state, while to the town kept its share.

The Civil War crippled Vermont with debt of a size never seen before, and the economy stumbled. State officials recognized the property tax was not sufficiently comprehensive to reach sources of wealth not directly related to land. Intangible personal property, such as stocks, bonds, bank deposits, and forms of credit, was included to the grand list of taxpayers, beginning in the 1880s. All resident and non-resident owners of shares of stock in all corporations, except railroad corporations, were taxed on what they owned.

This category of property, which included all forms of investment, was called intangible, because it was essentially an idea reflected on paper.

The problem with taxing intangibles was getting reliable information from taxpayers and from the towns. The taxpayer listed the property on a sheet and submitted it to the listers, who added that information to the grand list. Checking to see if the individual list was correct was impossible, and there was a serious consequence to being too candid, and towns were complicit in this race to the bottom.

Towns quickly figured out that if they kept their grand lists low, they could lower the amount of tax the state expected from them. To counter this tendency, and the natural shyness of people to disclose what they owned, the law was changed to require banks to disclose the money on deposit, mortgages, and bank stock, but stocks, bonds and notes continued to escape taxation. Governor John Barstow called this a “race of fraud” in 1882. Towns earned additional revenues from penalties for underreporting, but the disincentive of enforcement did not cure the problem. The first income tax was enacted that year, applied only to corporate franchises, including railroad, express, insurance, telegraph, telephone and steamboat companies, banks, savings institutions, and trust companies. The tax was based on gross income. In 1885, the state collected $200,000 from the corporate franchise tax and $171,000 in from the town grand lists, reflecting a radical shift in the burden of taxes from the individual to the corporation.

The use of the property tax for state revenues ended in 1931, when Vermont adopted the state income tax, and left the towns to tax property. By that time, the tax on the assessed value of corporations was the largest share of state revenue.

In 1991, the state property tax returned with the passage of Act 60. The grand lists of the towns, limited to real property, remain today the principal source of the tax.

Vermont towns can tax or exempt business inventory, machinery and equipment, from the property tax today. Today there is also an intangible element in taxable real property. Although not taxed separately, intangible interests such as a unit owner’s ownership share of a condominium association’s common assets are part of the fair market value of property.

A Note On Double Taxation: The Vermont State Supreme Court has rarely found double taxation to be unconstitutional. In 1990, the high court ruled that wood chips used by the city of Burlington in its generating plant were taxable. This was the most recent discussion of double taxation [up until 2010, at least]. Burlington claimed the proportional contribution clause of the Vermont Constitution and equal protection clause of the U.S. Constitution were violated by a law that taxes both the fuel used to produce electricity and the power itself. The argument failed. The Court refused to impose an “iron rule of equality,” as long as the classification was reasonable. It also ruled that even if this constituted double taxation, it would not be per se unconstitutional, if the legislature’s intent is clear.

Suggested Reading

- October 2019 WaPo article: “For the first time in history, U.S. Billionaires paid a lower tax rate than the working class last year” https://www.washingtonpost.com/business/2019/10/08/first-time-history-us-billionaires-paid-lower-tax-rate-than-working-class-last-year/

- Vermont Tax Rates and Charts https://tax.vermont.gov/research-and-reports/tax-rates-and-charts

- “Do Millionaires Migrate When Taxes Are Raised?” https://inequality.stanford.edu/sites/default/files/media/_media/pdf/pathways/summer_2014/Pathways_Summer_2014_YoungVarner.pdf

- “Millionaire Migration in California: Administrative Data for Three Waves of Tax Reform” https://inequality.stanford.edu/sites/default/files/millionaire-migration-california-impact-top-tax-rates.pdf

- “Understanding Long-Term vs. Short-Term Capital Gains Tax Rates” https://www.investopedia.com/articles/personal-finance/101515/comparing-longterm-vs-shortterm-capital-gain-tax-rates.asp

Read Blog Posts Related to this Project…

ARPA COVID Stimulus

BCS proposed graduated distribution of COVID stimulus funds and a "People's Budget" at the last…

This Post Has 0 Comments